FAMILY HISTORY

Unfortunately, those in our family who knew how our ancestors were addressed before the 18th Century have long left us. Some curious family members are still hoping to find relatives or others who might have some kind of documentation that might shed light on that part of our ancestry.

However, there has been adequate evidence and communication handed down through the years to indicate that they had, in fact, maintained their Zarathushtrian faith and Persian/Aryan heritage; and that they had been addressed by their ancient Persian and Zarathushtrian names.

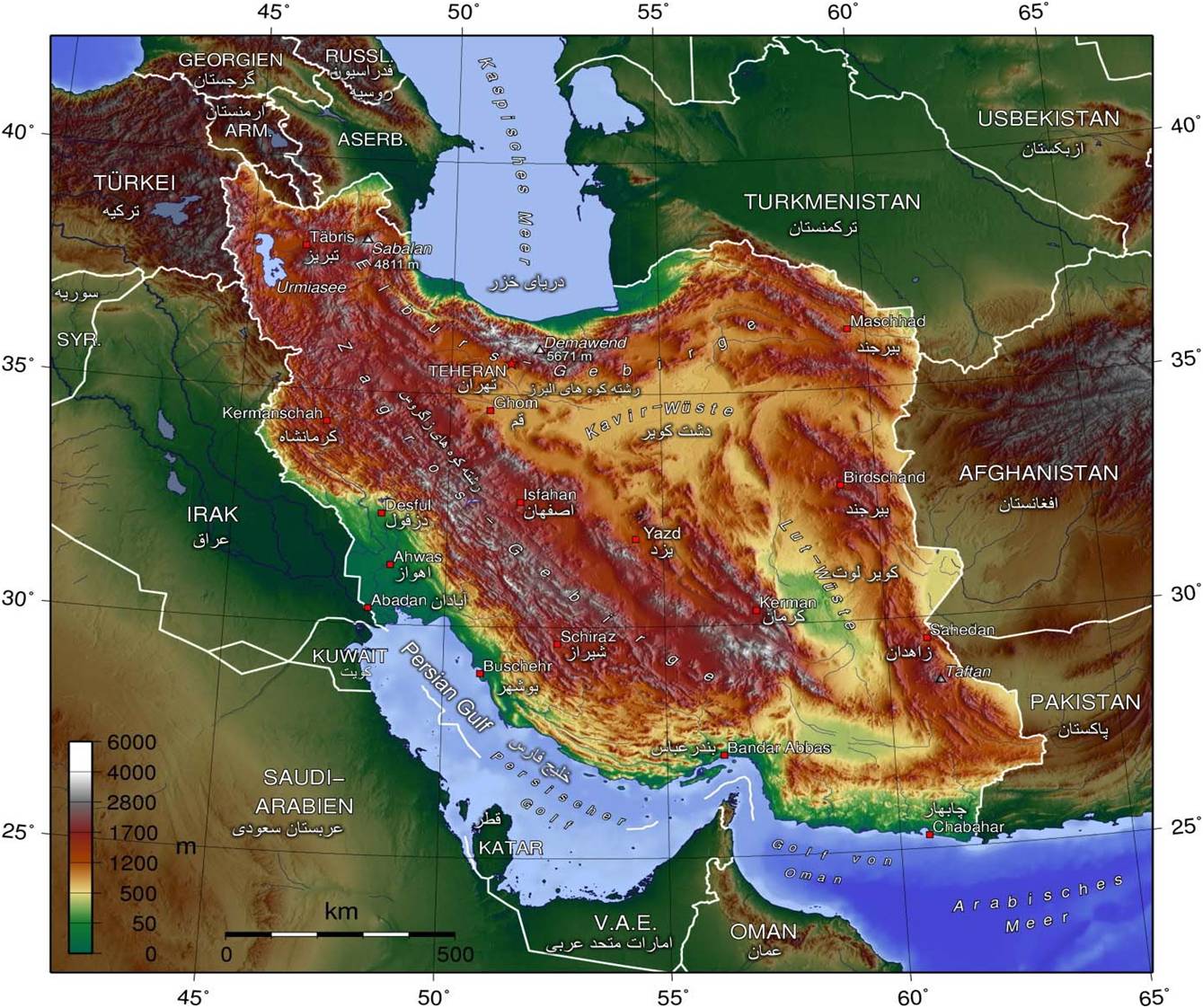

It has also been conveyed through generations that our ancestors hailed from the City of Yazd. There, they had been builders and architects, a trade passed down by their forefathers. And, because of their precision and skill, the title Ostad (Colloquially: Oossa) had been bestowed upon them by community elders.

Note: Ostad is the Persian word for Skilled Master -- it has an

One of the many building specialties of our family's Ostads was a ventilation system called Baadgir (windcatcher) -- a central air-conditioning method devised by Persian engineers more than 1,000 years ago.

-- Ancestor Ostad Mohamad

-- Ostad Mirza

(Married Soltan-Baigom Khalifeh-Soltani)

-- Haji Nabi

-- Mohamad

-- Ostad Sadegh

The fame of our Ostads soon spread beyond their local, even regional communities, and reached other provinces. They gained national recognition as first-rate architects, specializing in building and repairing intricate private and public structures, such as historical landmarks, monuments, mausoleums and mosques. One popular specialty was a precise architectural style called Kashikari -- the application of intricate, diverse mosaic tiles.

Among those whose fame spread nationally was Ostad Ahmad (son of Ostad Sadegh) who devoted his entire life to renovating historical and religious landmarks. His architectural achievements were manifold and prominent. But the one that brought him the highest honor was one summoned by Nasseraldin Shah, king of the Ghajars, the then ruling dynasty in Iran.

Assigned the responsibility of renovating Imam Ali’s Holy Shrine in Najaf, Iraq, Ostad Ahmad -- along with his designated committee including

Ostad Mirza-Zainolabedin and Ostad Essmail – went on an extensive journey and accomplished the task masterfully using Kashikari skills. Today, Ostad Ahmad’s signature is imbedded among the mosaic tiles of the mausoleum. Ostad Essmail took a wife in Iraq at that time and had several children. Thus, a branch of our family exists in that country – perhaps the subject of a possible research project for some curious family members in the future.

The Holy Shrine of Imam Ali in the city of Najaf, Iraq.

Samples of KashiKari

Some historical and religious landmarks built or renovated by our family Memars (architects)

Ancestor Ostad Mohamad and his son Ostad Mirza:

Ostad Ahmad, along with Ostad Mirza-Zainolabedin and Ostad Essmail, great grandsons of Ancestor Mohamad:

Ostad Mohamad, grandson of Ancestor Mohamad:

Ostad Mirza-Zainolabedin, great grandson of Ancestor Mohamad:

Ostad Abdolkarim, son of Ostad Ahmad:

Ostad Sadegh, great-grandson of Ancestor Mohamad:

Ostad Haidar-Ali, son of Shahrbanoo, great grandson of Ostad Mirza:

Before the advent of electricity, Baadgir was a highly popular method of combating the arid, warm climate in Yazd, and our family Ostads were the system’s highly sought-after specialists.

In fact, the fast-spreading reputation of the Ostads, especially three young brothers, as Baadgir specialists soon reached the neighboring communities and beyond, reaching a place called Jarghooyeh -- about 150 kilometers (94 miles) northwest of Yazd and about 60 kilometers (37 miles) southeast of the city of Esfahan.

Here is a picture of a Baadgir, installed on top of the Dolat-Abad Garden building in Yazd.

The Baadgir in this picture was built during the early years of the 20th Century in Jarghooyeh by Ostad Reza, son of Ostad Mohamad and great grandson of our ancestor. The picture was taken by Mansour Motamedi, grandson of Ostad Reza.

Over 1000 years ago, Persian engineers, being familiar with the Yakhchal technology, were able to master a new technique to cool their residences during hot summer months. The new approach was called Baadgir. A Baadgir (windcatcher or windtower) is a chimney structure positiond above the house and has four vents in four different directions. The vent situated opposite wind direction is opened manually to move air out of the house. That creates a negative pressure inside the tower, which pulls air from the basement and consequently from Ghanat. Finally, Ghanat draws its air from a distant access shaft as shown in Fig. 3, courtesy of Wikipedia, and the cycle is complete. The hot and dry desert air drawn into the Ghanat from the access shaft is cooled by contact with both the cool Ghanat walls and the water itself. Meanwhile, the air picks up enough moisture that helps cool the basement without creating a damp environment.

While Ghanats still play an important role in supplying irrigation water and providing a cooling system to people who live in remote and less populated areas of Iran, with the rapid development of deep wells the danger of lowering water tables by excessive pumping has been realized. As a consequence, the demise of this ancient engineering masterpiece is likely to happen in the near future.

Our ancestors used Ghanats to provide cooling for their residences as well as to preserve their perishable foods. Ghanats represent one of the oldest systems of water supply in the world. A Ghanat is merely a kind of subsurface drainage system whereby underground water is brought to the surface by means of a man-made gravity flow channel. The drains of the Ghanats are usually laid in the direction of maximum flow. Iranians and Syrians have known and utilized the Ghanat system of irrigation for thousands of years. Underground conduits are dug to introduce mountain underground water to the arid plains. Flow conditions in a Ghanat and the water profiles are represented in Fig. 1, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Fig. 1

In 400 BC, Persian engineers discovered Ghanats could also be used to store ice in the middle of summer in the desert. The ice was brought in during winter from nearby mountains and stored in especially designed, naturally cooled refrigerators calld Yakhchal. Yakhchal was a large underground space with thick insulated walls connected to a Ghanat and a system of windcatchers, Fig 2, courtesy of Wikipedia. The windcatchers drew cool air from the Ghanat and maintained low-level tempratures inside the Yakhchal. As a result, the ice melted very slowly and ice was available year round.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Baadgirs and Ghanats

Then, sometime during the late 1700s, some Jarghooyeh residents, including community elder Mirza Fathollah Khalifeh-Soltani, took a trip to Yazd and invited the three men to move to their hometown, to install Baadgirs in their community's residences and to improve Jarghooyeh's infrastructure.

The brothers accepted the job offers and left their environment in favor of moderate climate and successful careers. Hence they established residence in a village within Jarghooyeh called Mohamadabad.

However, the young men soon realized that the members of their new community -- all Moslems with Islamic names -- resented the newcomers’ religion and non-Islamic names. And, it was not long before residents of Jarghooyeh and the neighboring communities began warning the brothers about the negative consequences of not converting to Islam.

The pressure became enormous and the three young men decided to abandon their faith and names in order to be accepted in their new environment.

And so it has been said that during a formal religious ceremony, the three became Moslems. They were given the Arabic/Moslem names Sadegh, Nabi and Mohamad, and became widely recognized as Ostad Sadegh, Ostad Nabi and Ostad Mohamad. They were also bestowed the title Memar (Arabic for architect) and welcomed into the residents’ homes with open arms.

Regrettably, no further record has emerged surrounding the lives of Ostad Sadegh and Ostad Nabi, how they and their future generations fared or what family name or names they eventually adopted. However, they remained known as relatives and many newborns were named after them. Some word-of-mouth communication indicates the two may have moved from the Esfahan Province – possibly one to Kordestan and the other to Azarbayejan, both provinces of Iran. But, that search is out of the boundaries of this effort – perhaps the focus of a future effort... perhaps of an extended family search expedition.

Ostad Mohamad, hence, is the spotlight of this narrative as the only known ancestor of our family. He remained in Jarghooyeh, in the Village of Mohamadabad, where he started a family. He also became a very active and respected resident and his fame as a first-class Memar spread beyond his community. In fact, the burning question has been whether the village had another name and was renamed Mohamadabad in his honor… but then again that perhaps also could be the focus of another search adventure.

Although no documentation has surfaced concerning Ostad Mohamad’s birth date or when he died, it is recorded that he was buried in the Mohamadabad Cemetery. Also, it is not known how many children he may have fathered. The only record available is of one son whom he named Mirza, born in or around the year 1800.

Mirza learned all the ins and outs of the Memari (architecture) trade from his father, became an artful builder in his own right and earned the Ostad title. He also became a Persian literature and Persian poetry enthusiast, which he studied extensively, and gained fame as a well-versed literary man of his time.

Ostad Mirza took a wife from within his community by the name of Soltan-Baigom, the sister of the village elder Mirza Fathollah Khalifeh-Soltani whose son, Mirza Mohamad-Shafi Khalife-Soltani, grew up to become Mohamadabad’s Kadkhoda (village chief).

The exact number of children Ostad Mirza had is unclear, but we know he had five sons named Nabi (later became known as Haji Nabi), Ali-Naghi, Ghorban-Ali, Sadegh and Mohamad – all born between 1820s and 1840s. Ostad Mirza’s children also inherited their father’s literature and poetry enthusiasm and knowledge.

Details of Haji Nabi’s life, where he lived or when he died are not known, except that he had one son, Mohamad, whose destiny also remains a mystery. But, it is noted that Ostad Mirza’s other four sons followed their father’s trade and became skillful Memars, known as Ostad Ali-Naghi, Ostad Ghorban-Ali, Ostad Sadegh and Ostad Mohamad. And, from then on, all their descendants who mastered the Memari (architecture) trade were also addressed as Ostads. Additionally, the title Khanom, Banoo, Khatoon or Baigom (all variations of the Noble Lady title) were bestowed upon female family members.

A current view of Jarghooyeh -- picture taken in August 2010 by